For many wheelchair users, a simple flight of stairs isn’t just an architectural feature; it is the “final boss” of independent mobility. But if you assume the quest to conquer gravity began with modern robotics, you might be surprised to learn that this battle has been waged for centuries. While King Henry VIII dabbled with a primitive “chairthrone” at Whitehall Palace, the true story of the stair-climbing wheelchair is a saga of grit and sheer kinematic ingenuity.

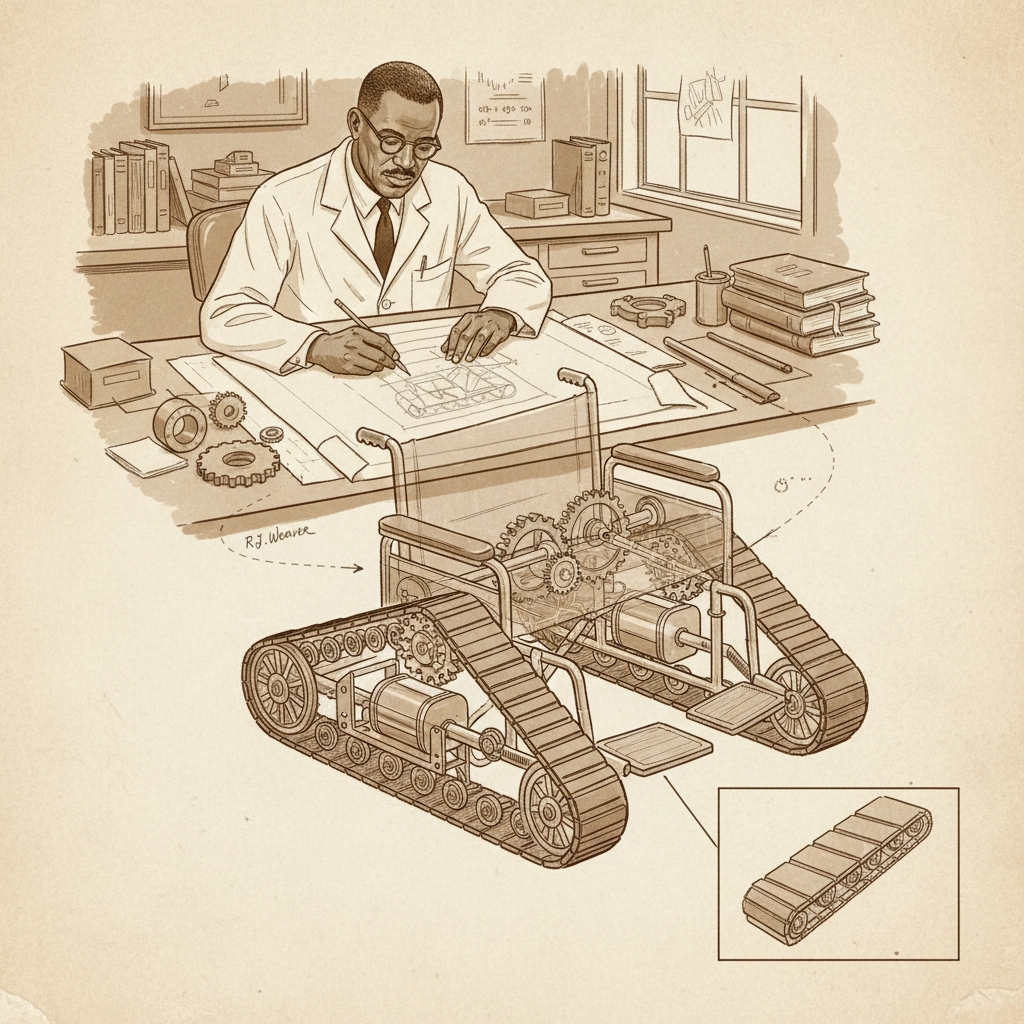

It didn’t start with the high-tech iBOT. The real revolution began with overlooked visionaries like Gourley H. Green and Rufus Jack Weaver, whose 1960s patents laid the groundwork for the machines we see today. From the early days of tank tread wheelchair design sketches to the complex peristaltic propulsion of modern prototypes, the road to accessibility has been paved by inventors who refused to take “no” for an answer. Ready to see how we got from 1964 blueprints to AI-driven crawlers? Buckle up—we’re diving into the forgotten history of the engineers who finally gave wheels the power to climb.

The Short Answer

If you are looking for the “encyclopedia entry” version of this story, here it is. While no single individual can claim sole credit for the entire genre of assistive mobility device innovation history, the earliest significant patents for self-propelled stair-climbing wheelchairs belong to Gourley H. Green (filed 1962, granted 1964) and Rufus Jack Weaver (1968).

Before these patents, Ernesto Blanco at MIT developed a working concept in 1962 using a “quasi-planetary” wheel system, though it never reached mass production. The technology took a massive leap forward in the 2000s when Dean Kamen introduced the iBOT, utilizing gyroscopic self-balancing technology. Today, the invention is a cumulative masterpiece of engineering, combining continuous track mobility device designs, spider wheels, and intelligent sensor systems.

Read On

But dates and patent numbers only tell half the story. The real magic lies in the “why” and the “how.” I’m going to take you through the crazy prototypes, the forgotten inventors, and the “Transformers-style” tech that is finally making this dream affordable. If you’re interested in the broader evolution, check out our complete wheelchair series.

The Ancient Quest: When Wheels Met Stairs

Long before we had batteries or microchips, humans were trying to figure out architectural barrier navigation. It turns out, the desire to get upstairs without being carried like a sack of potatoes is as old as multi-story buildings themselves.

King Henry VIII’s “Chairthrone”

In the 16th century, King Henry VIII of England faced significant mobility challenges later in life. His solution? The “stair lift” of the Renaissance. Historical records from Whitehall Palace describe a block-and-tackle system—a “chairthrone”—that allowed servants to haul the monarch up and down a 20-foot staircase. While it wasn’t self-propelled, it highlights that vertical mobility solutions have always been a priority for those with power.

The 1655 Breakthrough

We have to give a massive nod to Stephan Farfler, a paraplegic watchmaker in 1655. He built the world’s first self-propelled wheelchair. While it didn’t climb stairs, his three-wheeled, hand-cranked invention proved that users didn’t need to rely solely on pushing attendants, setting the stage for every chapter of mobility independence engineering that followed.

The 1960s Boom: Meet the True Pioneers

The 1960s wasn’t just about the moon landing; it was the golden era for accessibility concepts. This is where the stair climbing wheelchair went from sci-fi fantasy to patent-pending reality.

Ernesto Blanco’s MIT Concept (1962)

At MIT, a brilliant mind named Ernesto Blanco was tackling the physics of the problem. He designed a spider wheel mechanism—technically a “quasi-planetary” wheel frame. Imagine a wheel made of smaller wheels that rotate around a central axis. Blanco proved that you didn’t need tracks to climb; you could “step” up the stairs if your wheels were smart enough. Although he only built a small scale model, his work validated that robotic stair climbing aids were mechanically feasible.

Gourley H. Green’s Vision (1964)

In 1964, Gourley H. Green was granted Patent US-3142351-A. If you look at the blueprints, you see the grandfather of the modern electric stair climber. Green’s focus wasn’t just climbing; it was autonomy. He envisioned a “self-contained” battery-operated system that didn’t require external ramps. His Gourley H. Green invention history is often overshadowed, but his insistence that the device should function as a normal wheelchair on flat ground was revolutionary.

Rufus Jack Weaver (1968)

Then came Rufus Jack Weaver. A Navy veteran and a Black inventor, Weaver filed Rufus Jack Weaver patent 3411598 in 1968. His motivation was deeply personal and social: he wanted to dismantle the physical segregation caused by stairs. Weaver’s design was robust, intended to give disabled individuals access to public buildings that ignored their existence.

The “Crawler” Era: Tracks vs. Wheels

By the 1980s, engineers looked at the problem and thought: “Why reinvent the wheel when we can use a tank?” This era shifted toward the continuous track mobility device.

The logic was simple: wheels slip, but tracks grip. By using an “endless belt crawler” (essentially rubber tank treads), engineers could distribute the user’s weight over multiple stair edges simultaneously.

We cannot discuss tracks without mentioning the Japanese contributions, specifically Rintaro Misawa. Through his company, Sunwa Sharyo, Misawa filed multiple Rintaro Misawa patents for carrier-style stair climbers. The Sunwa Sharyo crawler system prioritized stability over speed, becoming the standard for emergency evacuations.

The Trade-off

So, why don’t we all use tracks? Tracks have a massive downside: friction. On a staircase, they are kings. On a living room carpet, they are a nightmare. Turning a tracked vehicle requires “skid steering,” which tears up floors and drains batteries. This engineering dilemma—grip vs. maneuverability—stalled progress for years until hybrid designs emerged.

The Control Revolution: Preventing the “Tumble”

Let’s address the elephant in the room. The biggest barrier isn’t the motor; it’s the user’s fear of falling backward. Tilting back 45 degrees while suspended in the air is terrifying.

In 1992, Douglas J. Littlejohn and his team filed a patent that changed the game. They introduced the tilt sensor safety mechanism and an automatic seat leveling system. Before this, the user tilted with the chair. Littlejohn’s system used actuators to keep the seat horizontal while the wheelbase angled up the stairs. This meant that even if the chair was climbing a steep flight of subway stairs, the user felt like they were sitting on flat ground.

Dean Kamen and the iBOT: The “Segway” of Wheelchairs

If you know one name in this industry, it’s probably Dean Kamen. Before he gave the world the Segway, he applied his genius to the Dean Kamen iBOT technology.

Launched in the 2000s, the iBOT utilized gyroscopic self-balancing wheelchair tech to balance on two wheels, allowing it to climb stairs by rotating its wheel clusters over each other. It also allowed users to “stand” at eye level with peers, offering a psychological liberation that went beyond simple mechanics.

The Student Revolution: Enter Scalevo and Scewo

Just when the industry seemed stagnant, a group of students from ETH Zurich proved that you don’t need a massive R&D budget to innovate. In 2015, they unveiled the Scalevo prototype development.

The Scalevo evolved into the Scewo BRO. Here is the genius part: it drives on two big wheels for agility on flat ground. But when it hits stairs, it drops a massive set of rubber tracks from its underbelly. The Scewo BRO features represent the pinnacle of hybrid leg-wheel mechanism logic. It looks like something out of a sci-fi movie and has finally brought sex appeal to assistive mobility device innovation history.

How Do They Actually Work? (A Simple Guide)

- 1Continuous Tracks: Think of a bulldozer. Uses a crawler system for incredible grip but is heavy and hard to turn indoors.

- 2Spider/Cluster Wheels: Imagine three small wheels arranged in a triangle. As the axle rotates, the top wheel “steps” over to become the bottom wheel.

- 3Levelling Systems: Hydraulics or linear actuators push the seat forward to counteract gravity, essential for any wide seat electric wheelchair to prevent tipping.

- 4Morphing Wheels: Bleeding edge tech where the wheel itself changes shape from round to “clawed” using morphing wheel technology.

Why Aren’t They Everywhere? (The Challenges)

If patents existed in 1968, why are we still building ramps?

- The Price Tag: A reliable stair climber often starts at $15,000 and can exceed $30,000. Insurance companies often view them as “luxury items.”

- The Weight Problem: To lift a 200lb human plus a 100lb chair requires massive power. While we have lightweight ergonomic electric wheelchair models, adding climbing gear doubles the weight.

- The “Trust” Issue: Would you trust a machine to dangle you over concrete steps? This is why FDA cleared stair climbers undergo rigorous testing.

Modern Evolutions: AI and The Internet of Things

We are now entering the era of smart mobility aids. Modern chairs use LiDAR and intelligent sensor systems for wheelchairs to “see” the stairs before the user even gets there. Imagine a chair that calls for help automatically if its sensors detect an anomaly—that is the reality of IoT integration.

For those needing immediate solutions, mobile stairlift alternatives and the all-terrain electric wheelchair (like the Caterwil GTS) are bridging the gap between standard mobility and full robotic climbing.

Conclusion

The invention of the stair-climbing wheelchair wasn’t a single “Eureka!” moment. It was a 60-year relay race. It started with Gourley H. Green and Rufus Jack Weaver dreaming of access in the 1960s. It passed through the labs of MIT with Ernesto Blanco, survived the heavy industrial tracks of the 80s, and found its balance with Dean Kamen.

Today, students and engineers are using AI to finish what those pioneers started. This technology isn’t just about mechanics; it is about dignity. It is about looking at a flight of stairs and seeing a path, not a wall.

If you found this history fascinating, share this post. The more people understand the evolution of power wheelchairs, the more demand we create for affordable accessibility. And remember: independence is always worth the investment.